A big country lay ahead of us and the distances we had here gave us respect. We also had not planned to visit a major attraction here, so we’ve been prepared for many days that are all about making kilometers.

Contrast border

Arriving at the border, we first had to exchange our money. We had a significant amount of Rwandan francs with us, because I was not sure how far away the nearest ATM in Tanzania was. Fortunately, there were a few exchange offices, and I got one of them to round up so we had minimal loss. A little later, the lanes crossed clearly with arrows – from now on there is left side traffic until South Africa. Finally, we crossed the Rusumo River, one of the strongest tributaries to Lake Victoria, and were in Tanzania, where all checks are done in one building.

For five days we had overstayed our East African visa, but it was clearly stated on the official website of the Rwandan Ministry of Immigration that this had no consequences. The border policewoman did not see this so relaxed and asked me urgently why. I claimed to have been ill, which she did not accept. “You have to pay me $50 now” – I immediately smelled corruption. In comparatively disciplined Rwanda even a rather shameless attempt: no serious border guard would state an amount without basis and ESPECIALLY NOT use the pronoun “me”! I asked her calmly about the legal basis for this amount. With this I hurt her authority. She started a triad about how I would have the nerve to ask her about the law and what it would be like when she overstays a visa in Germany and that I just want to overstay. Despite everything, she stamped our passports without consequences or negative notes and left everything at a verbal warning. I figured she realized that we knew the law, pulled the emergency brake and let us go. Corruption is severely punished in Rwanda, and if things escalated further, she would probably be fired and land in jail. Especially because of that, this try surprised me a lot.

The Tanzanian side was much friendlier and very simple. All we had to do was pay $50 per person and sign. A few minutes later we had our passports back with an entry stamp. It is said that Tanzania has a visa on arrival. In my opinion, it is only an entry fee, since no conditions are necessary. Anyway, from now on we can spend three months in this country. After a quick lunch in the border town we were on the way again.

I’ve heard it before, you can tell immediately how much lower the population density is here. Within a few kilometers we were in unspoiled nature and had silence around us. No hooting children or whistling men, it was lovely. And even when we finally arrived in a village, some people looked curiously, but generally left us in peace and moved on. When we met schoolchildren along the way, most of them just waved shyly, almost nobody ever followed us. We could stop, take a break and camp where we wanted, no one was staring at us and we generally had our rest. How fantastic! I said to Yuily, “In this land we are human again.”

- The border

- Empty nature

- Rainy season

- Truck road

Pleasant Tanzania

We spent the first two nights in guesthouses. Accommodation and simple restaurants are, at least on the main roads of Tanzania, cheap and very frequent. This road is the lifeline of Rwanda and Burundi, with much of their imports coming through here in trucks. So we were very happy with the infrastructure that the traffic brings, and many of the drivers were very friendly and spoke good English.

However, very few other Tanzanians spoke good English. Swahili is effectively the only official language in the country, so we had to dig the few words we learned in Kenya out from memory and learn some new ones as quickly as possible, which Yuily did very well. Wali Maharage, rice with beans, was a dish that was found in the smallest villages, and to camp we asked “Kesha Kulala?” while pointing to the desired spot. Like this, we could camp on the lawn of a gas station on the third night. And although our tent was visible from the street, no one came to stare (in Rwanda, the tent would be surrounded within minutes by gawkers).

From the border to Nyakanazi, the road was in poor condition with many potholes and gravel. In Nyakanazi was also the turn to the road T9, which is the most direct route to the Zambian border. The problem is that the T9, just like the T6 south of Tabora, is largely unpaved and the rainy season has just begun. After my Kenyan mud bath I did not look forward to another, and since we had the time anyway, we decided to cycle on paved roads east to Dodoma, from where we would turn to the southwest.

After this turn, the road was also in excellent condition thanks to EU aid. The hills subsided and we often cycled on a wide shoulder of the now flat road to the east. The rainy season had definitely arrived, so we often had to seek shelter and sat once in the tent until 1 pm because it did not stop raining. The rain was neither reliable nor daily, so after the city of Kahama we had several days of crazy heat in an almost cloudless sky.

- Food available in small villages

- Gas station camping

- Mining village

- Flat nice cycling

- Wild camping

- Picture perfect Africa

- Many cyclists

- Simple conditions

School, poverty and hospitality

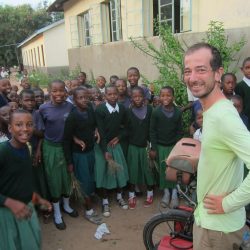

Schoolchildren were often seen in Tanzania and I have heard the inhabitants of neighboring countries rave about the education system in Tanzania. There is compulsory education and generally no tuition, state schools are well-equipped compared to Kenya and Uganda and the children wear clean, tidy uniforms. We camped a few times in schools. Of course, while the kids were incredibly curious, none of them made fun of us,shouted “Mzungu!” or touched our bicycles. If only one assumption remains, I found myself confirmed in my theory from Rwanda: here, despite our skin color, we were treated with respect and dignity, because education in Tanzania attaches importance to it.

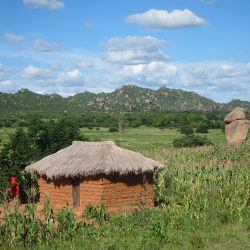

Unfortunately, wealth distribution stops with the school system. Many parts of the rural population live in poor mud houses, which, despite existing lines, are not connected to the electricity grid. When we asked for drinking water, we often got rainwater or chlorinated well water. These people are poor, although Tanzania is not really a poor country. The government should be ashamed here. Nevertheless, people almost never begged: The only times we were begged at were by obviously crazy or drunk persons. The other inhabitants in the places where this happened knew these idiots and often went out of their way to help us them get rid of them.

Over time, the landscape changed. We cycled from time to time for a few dozen kilometers through a semi-desert in which baobab trees and thorn bushes dominated the landscape, which was still very green thanks to the rainy season. When it was not raining or cloudy, it was often too hot for cycling at lunchtime and so we rested for several hours in a shady spot, preferably with an ice cold soda. If it was raining, then so hard that we had to seek shelter. It was even sometimes chilly enough to put on a jacket. A cloudy day was mostly ideal.

During this time we received extraordinary hospitality from Tanzanians: A woman spotted us camping near a church and promptly invited us to her home where we camped. The same thing happened one night later, when a student addressed us with fluent English and invited us. Finally, at a Catholic mission, we asked for permission to camp, which was immediately followed by “Of course!” To our surprise, one of the nuns was from Italy and 90 years old. Sister Rita helped build this mission, which includes a large farm, kindergarten and modern clinic. Of course they did not let us camp like other Catholics in Africa so far, but showed us a room and invited us to dinner. Thank God!

- School

- Excited, but polite kids

- Semi-Desert

- Sister Rita

The inconspicuous capital

After a little more than two weeks cycling, we finally arrived in Dodoma. I had contacted a host from warmshowers here and was surprised that a Nepalese family opened the door for us. They lived here for over two years and had a large plot. They let us stay in a small building on the edge of the property and invited us to a barbecue. The family had to travel to Dar es Salaam the next morning – we asked if we could stay a week and the answer was positive. Excellent! Dodoma is the capital of Tanzania, but you would not expect it. There are no major buildings or embassies here, and even some ministries are missing – all that remains in the coastal economic capital, Dar es Salaam. Similar to Naypyidaw in Myanmar, Dodoma is just a capital on paper.

During our break in Dodoma we also took care of Zambian visas. Some citizens, such as Germans, can receive an uncomplicated visa upon arrival, but not Taiwanese – so Yuily must apply for the visa in advance. Fortunately, this is possible online, so we uploaded the documents, such as cover letter, photo and passport copy, paid online and waited. My visa was approved after an hour, while Yuily still had to wait for an answer. We set off on the way.

- Our home …

- … for a week

- Thank you!

- Cycling out with Rakesh

From Dodoma to Iringa we finally left the main road between Dar es Salaam and Kigali after almost 1000 km and consequently the traffic was now much quieter. This road also traverses a relatively low plain with only 600 meters altitude, in which the high temperatures of approx. 36°C was a challenge for us. Tanzania continued to be at its best. After ordering a few drinks in a village pub, a group of teachers invited us to the table and after a short conversation they gave us drinks and one of them invited us to their home for the night. The next night we asked to camp at a school – after the director was found, he even wanted to give us his bed, which we objected to in protest. Thanks to your great hospitality, dear Tanzanians!

Around Mtera we unfortunately noticed that the schoolchildren begged and demanded money. “Mzungu! Money!” That was sad, because that was never the case so far in Tanzania. I can only speculate, but since it was mostly students with the same uniform, the reason was obvious: There was probably a foreigner working as a volunteer in this school, who has distributed pens, notebooks, sweets and possibly even money to the children. Here again an appeal to all: Do not give gifts to children in Africa!!! You are ruining their lives! It creates an image at an early age that the white man always brings things and you never have to take care of them yourself. Even useful items such as notebooks and pens contribute to this. Every village shop in Tanzania sells these things for little money. Africa has to stand on its own feet, and with every pen given to a schoolchild, that’s exactly what we prevent.

- Dinner from spontaneous hosts

- The frying pan

- Back into the mountains

- Wild camping

A little later, Yuily received the answer to her visa application. This answer had a big effect on our future plans …